A Spiritual Journey of the Body and Soul

Lisa Bowles

What was it that drove men and women alike to leave all their belongings behind them and embark upon an extensive and often dangerous trip to the holy land?

For many, the pilgrimage

was a journey that entailed not only a physical

movement

from one place to another, but also a journey of the soul. It was a

spiritual journey many took to pursue God and to get to know Him

better, as much of the Church in medieval times was in turmoil and

did not present a clear picture. As defined in The Stripping of

the Altars, the primary purpose of a pilgrimage had always been

"to seek the holy, concretely embodied in a sacred place, a relic or

a specially privileged image" (121). This religious journey often

transcended into the sacred and the personal, as we see in both

The Book of

Margery Kempe and Chaucer's Canterbury

Tales, particularly with the Wife

of Bath's Tale. The Catholic

Encyclopedia

explains the pilgrimage this way: "Pilgrimages may be defined as

journeys made to some place with the purpose of venerating it, or in

order to ask there for supernatural aid, or to discharge some

religious obligation." Over time, however, these pilgrimages became

increasingly commercialized and driven by motives with monetary

rewards.

Margery Kempe and Alison of Bath experience the pilgrimage in largely different ways, though their narratives both are framed in the context of the ideal spiritual journey. Both Medieval women set out to conquer their journeys, pitting themselves against society and the conventions of wifery to seek the unknowable. Their motivations, passions, and experiences reveal much about their characters, and fall somewhere within the boundaries of the ideal and the practical. Both women exist textually because they have, indeed, encountered a spiritual pilgrimage characteristic of their time, and this pilgrimage in many ways defines their character. How did the journey enhance their religious conceptions? What provided the pilgrims with the motivation to sacrifice so much of what they had perceived for so long as society's symbols of status? If the pilgrimage was so rich and inspiring, why is it that there are so few modern day pilgrims?

It has been said that the pilgrimage begins in the heart. The Catholic Encyclopedia explains that "the Incarnation was bound inevitably to draw men across Europe to visit the Holy Places, for the custom itself arises spontaneously from the heart. It is found in all religions." The pilgrim experiences an insatiable desire to experience the holy, and the thought of the hardship and consequence makes it all the more noble and holy a task. James 1:2-6 reads, "Consider it pure joy, my brothers, when you face trials of many kinds, because you know that the testing of your faith develops perseverance..." Romans 5:3 and 8:18 say, "...we also rejoice in our sufferings, because we know that suffering produces perseverance; perseverance, character; and character, hope...I consider that our present sufferings are not worth comparing with the glory that will be revealed in us." These verses provide the pilgrim with the Biblical motivation to embark on a pilgrimage, though there were several motivations for a pilgrim to set out. The journey began to be looked upon as a purifying act, almost an atoning for the pilgrims' sins when they visited the relics of the saints. They, too, sought blessing from God in the journeys, as many of them read, "Blessed are those whose strength is in you, who have set their hearts on pilgrimage" (Psalm 84:5). They wanted to seek the holy, to experience God, to purify their souls.

Sometimes pilgrims were sent to the holy lands as a punishment; the hardship and cruel experiences were enough to help someone repent for their own sins. The pilgrimage was an intense journey not possible for the weak and ill-motivated. In LETTER XXII. TO EUSTOCHIUM, the unknown pilgrim says, "Many years ago, when for the kingdom of heaven's sake I had cut myself off from home, parents, sister, relations, and--harder still--from the dainty food to which I had been accustomed; and when I was on my way to Jerusalem to wage my warfare..." This expresses clearly a common attitude towards the journey. He cut himself off in order to wage war; he was a pilgrim with a cause and heartfelt motivation.

Ideally, the pilgrimage was a sincere journey towards a deeper

knowledge and experience of God, arising from a deep desire to feed

the soul its spiritual needs. This is made clear in Margery Kempe's

vivid and detailed account of her journey towards Christ. Her

book is clearly more  than

a historical account or chronological detail, but speaks as more of a

journal entry or a story passed down to the generations as a

spiritual autobiography. Margery Kempe was a woman who lived her

faith wholeheartedly and stopped at nothing to please her God. Note

her words to her Lord, "Ah, blissful Lord, I would rather suffer all

the cutting words that people might say about me, and all clerics to

preach against me for your love...for the respect of this world I set

no value at all" (176). This devotion meant a desire straight from

her heart to give all that she had for service and love to God.

Through her frequent fits of weeping and wailing over the condition

of the world and her meditation on the passion of Christ, her

devotion was displayed to the public. This, in turn, exposed her to

ridicule. Her lack of concern for the ways the world treated her

shows an extreme devotion, indeed one required of a true pilgrim.

than

a historical account or chronological detail, but speaks as more of a

journal entry or a story passed down to the generations as a

spiritual autobiography. Margery Kempe was a woman who lived her

faith wholeheartedly and stopped at nothing to please her God. Note

her words to her Lord, "Ah, blissful Lord, I would rather suffer all

the cutting words that people might say about me, and all clerics to

preach against me for your love...for the respect of this world I set

no value at all" (176). This devotion meant a desire straight from

her heart to give all that she had for service and love to God.

Through her frequent fits of weeping and wailing over the condition

of the world and her meditation on the passion of Christ, her

devotion was displayed to the public. This, in turn, exposed her to

ridicule. Her lack of concern for the ways the world treated her

shows an extreme devotion, indeed one required of a true pilgrim.

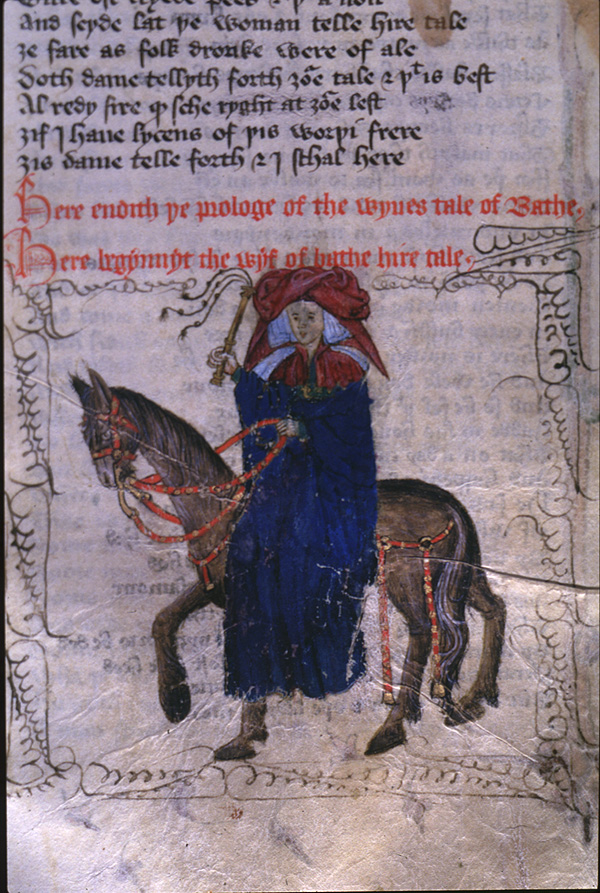

On the other hand, it is questionable as to whether the Wife of Bath's motivations for the journey are worthy of the praise due to a truly pious individual. Hstpaul.gifer collection of four previous husbands challenge scholars as to whether she was on the journey to find another husband rather than to become a more true worshipper of God. Her frequent twisting of Scripture to work for her advantage is another indicator that the Wife of Bath's motives for pilgrimage were less than notable. Finally, her desire for social control and acceptance shows a concern for the world's standards rather than for God's, in contrast to Margery Kempe's sole desire to come closer to the holiness of God. Much of Alison's talk is of marriage, sex, and commerce, indicating where her passions lie. She often manipulates conversations with her fellow travelers, and insists on keeping the attention when it is her turn to speak. Even her tale itself is one of female dominance and "masterie," when it would be more noble if her thought and concerns were for God's dominance and masterie as she sought to find him on her journey. She does show an affection for the pursuit of God, usually though, when she is trying to prove a point for herself. Consider, "Lat hem be breed of pured whete-seed,/ And lat us wives hoten barly-breed./ And yet with barly-breed, Mark telle kan,/ Oure Lord Jhesu refresshed many a man" (lines 143-146). In this example, Alison is speaking of how a wife can refresh a man by having sex with him because she is likened to barley bread; Jesus talks also of refreshing others with bread, but not at all in the same case. This is one of several instances in which the Wife of Bath used Scripture to establish her own argument.

The Wife is not the only in her traveling party to enjoy the praise of others; perhaps it is a social condition of her time that lessens the spiritual meaning of the pilgrimage for all involved. It is questionable even that the friar or the priest on the journey have motivations desirable of the noblest of pilgrims. In contrast, Margery Kempe talks little of traveling companions or the motivations of others, other than when she expresses her disdain at the lack of spiritual concern in the church of her day. Therefore, she presents a purer view of the idea and even follows it. Alison participates in the act of the pilgrimage, but little is shown to be of true or noble motivation according to the ideal motivation of a pilgrim.

Another aspect of the pilgrimage that progressed into an advanced form of intervention was the pursuance of the journey for the soul of another; this was called a surrogate pilgrimage. Often times those who were unable to go on the journey, or who could not afford it, would pay stipends to those going to bid them to pray for their souls at the shrines of the saints. Beginning merely as an opportunity to take part in the pilgrimage without actually going, this action became more and more common as people began to believe that the intervention of the pilgrims would, in reality, save their souls. They began to pay them large sums of money for their prayers, bringing in another secular twist to the holy endeavor as the money changing was often misused. A story is told of one man who journeyed to Compostella for the souls of three of his family members. He was awakened one night with a dream of his uncle, then dead, urging him to go back to the site to pray and release him from Purgatory. It also was not uncommon for a pilgrim to promise healing upon the arrival of the journey. The saints, when prayed to and worshipped, had the power to heal. This was soon a money-gathering endeavor as many promises of healing were made and then not delivered. It is thought that many pilgrimages were financed through these surrogate methods, which drove them to increasingly become more commercialized and less spiritual, personally, for the pilgrim.

Neither of these purposes are mentioned much in either Margery Kempe or The Wife of Bath's Tale however it is likely that they played a part in the process. Margery speaks much more of her encounter with the saints, whether she was praying to them for her own needs or for the needs of others. She is shown many times weeping at the feet of the saints or at the sign of a crucifix, and often prays for others. She meets many people along the way, uses her resources wisely, and was probably funded by few of her loyal friends. It is much more believable that Alison was involved in the pilgrimage for the financial and adventurous benefits, as she was an industrious and headstrong woman, not hesitant to manipulate or take advantage of another. In contrast to Margery, she talks little of the saints and more of herself. Many scholars say that this pilgrimage was a part of her plan to attain another husband, or even to get rid of her current one. Her status as a previous widower, several times, puts her in a favorable financial position; there fore it might not be as likely that she was financed in her pilgrimage. One can only speculate, however.

The progression of the pilgrimage can also be traced to the change in numbers of participants. The Catholic

Encyclopedia states that these journeys were, at first, a mere

issue of individual traveling. Yet in a short period of time, they

developed into larger productions organized properly by companies.

The Wife of Bath and Margery Kempe illustrate both of these phases

quite clearly. Margery was most definitely the lonely pilgrim

traveling individually, while Alison was the pilgrim connected to the

larger group moving together toward the common goal. Many times,

states the Catholic

Encyclopedia, "The initiators were clerics who prepared the whole

route beforehand and mapped out the cities of call. The bodies of

troops were got together to protect the pilgrims." It is not known

whether this was the case with Alison and the other travelers, but it

is quite possible. It is known that the guide in the journey was a

tavern keeper, though only a guide rather than a cleric initiator.

Hers was a varied crew, no doubt Chaucer's attempt to comment on his

contemporary society. The cross-section appearing in The Canterbury

Tales is a lively bunch that would seemingly not have gotten together

on their own. On the other hand, Margery again displays the purer

form of the pilgrimage in that she does travel alone and for strict

purposes. Hers is the original form of the journey though she is

tainted along the way, many times, by her more modern

counterparts.

traced to the change in numbers of participants. The Catholic

Encyclopedia states that these journeys were, at first, a mere

issue of individual traveling. Yet in a short period of time, they

developed into larger productions organized properly by companies.

The Wife of Bath and Margery Kempe illustrate both of these phases

quite clearly. Margery was most definitely the lonely pilgrim

traveling individually, while Alison was the pilgrim connected to the

larger group moving together toward the common goal. Many times,

states the Catholic

Encyclopedia, "The initiators were clerics who prepared the whole

route beforehand and mapped out the cities of call. The bodies of

troops were got together to protect the pilgrims." It is not known

whether this was the case with Alison and the other travelers, but it

is quite possible. It is known that the guide in the journey was a

tavern keeper, though only a guide rather than a cleric initiator.

Hers was a varied crew, no doubt Chaucer's attempt to comment on his

contemporary society. The cross-section appearing in The Canterbury

Tales is a lively bunch that would seemingly not have gotten together

on their own. On the other hand, Margery again displays the purer

form of the pilgrimage in that she does travel alone and for strict

purposes. Hers is the original form of the journey though she is

tainted along the way, many times, by her more modern

counterparts.

Both women appear to share many things in common as they are both large literary figures of the late Middle Ages who participated in a highly spiritual endeavor. Upon closer inspection, however, we see that they differ in many ways that set them apart as different and separate pilgrims. Each reflect the portrait of a pilgrim outlined in Hebrews 11:13-16 in the statement, "...They admitted that they were aliens and strangers on earth. People who say such things show that they are looking for a country of their own. If they had been thinking of the country they had left, they would have opportunity to return. Instead, they were longing for a better country--a heavenly one..." Both women were, in fact, longing for a country not yet their own, and we can imagine that they took heart in this verse. Similarly as well, both Margery and Alison fit the description of the pilgrimages' tendency to become an escape, as stated in The Stripping of the Altars,

"Pilgrimage also provided a temporary release from the constrictions and norms of ordinary living, an opportunity to review ones life and, in a religious culture which valued asceticism and the monastic life above the married state, an opportunity for profane men and women to share in the graces of renunciation and discipline which religious life, in theory at least, promised" (191).

The medieval pilgrimage, though much different from its original intentions, is appealing to both the pilgrim of its time as well as the modern pilgrims of today. Many people, "religious" or not, consider themselves to possess a spiritual dimension of their soul which they try in many ways to explore and satisfy, much in the same way as Margery and Alison do. Few, however, devote the time and sacrifice characteristic of Margery to the pursuit. Alison's influence can be seen more clearly in our day as the "groupthink" attitude and moral relativism have spread amongst the more modern pilgrims. They explore different groups, attitudes, and beliefs, and more often than not, come to the conclusion that any belief is good for anyone. Everyone can believe what they want to without holding to a common standard of good or right and wrong. Both the Wife of Bath and Margery Kempe would probably scowl at this lazy pursuit of the holy and meaningful as both women wholeheartedly pursue, in their lives, what they tend to have a passion about. These pilgrims, though so different in motivation and execution of their own pilgrimages, outline a framework within which we can judge our own spiritual pursuits.

Are we more like Alison, along for the ride, using religion as a means to personal gain and satisfaction? Or are we like Margery, deeply committed to the pursuit of knowing something or someone who is holy and personal? As the medieval pilgrims journeyed through hardship to meet the spiritual needs of their souls and others', so we should consider the pilgrimage and what place it has in society today. The pursuit will not be in vain. It is proven, through the lives of both Margery Kempe and the Wife of Bath, that there is much to be learned and attained from taking a trip such as theirs. As stated in The Stripping of the Altars, "travel to seek the sacred outside one's immediate locality had important symbolic and integrative functions, helping the believer..." (191).

Works Cited